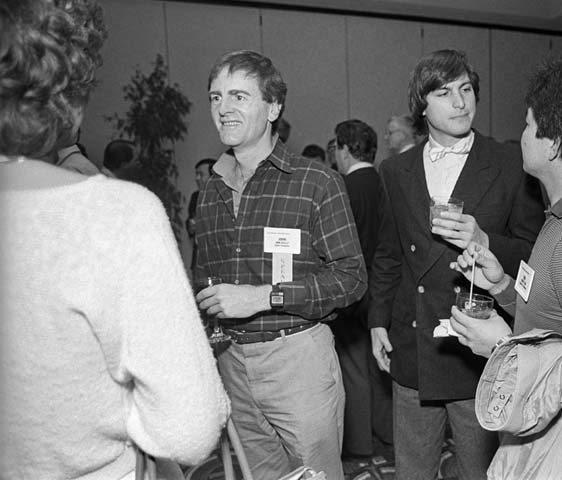

Flashback to Esther Dyson’s PC Forum, 1984, year of Macintosh launch. From left: Nancy Keene; John Sculley, Apple; Steve Jobs; Apple; Robert Toda, Seagate Technology. Photograph © Ann Yow-Dyson

I had a ringside seat during the ramp-up of the personal computer industry — serving as public relations counsel to CEOs and entrepreneurs who were re-inventing the way we would do business in the modern world. A pretty heady experience for a young, non-engineering female, not to mention an amazing learning laboratory.

A key barometer of industry clout was Esther Dyson’s PC Forum, where the elite players would convene, preen and be seen.

You could see early on that Steve Jobs was a different kind of cat. He had an aura of cool amid a sea of self-proclaimed tech geeks. He was a marketing impresario, not a programmer. A liberal arts major, not an engineer or MBA. He even dressed differently. (Note blazer and bow tie, forerunner of the black turtleneck, in photo above.)

He didn’t play nice with the other kids. When the industry moved toward standards and compatibility, Apple stood alone with a proprietary system. When the IBM “clones” (Compaq, Dell, HP, DEC et. al.) dominated the high-volume Enterprise sector, the Mac was beloved by students, graphic designers and creatives, a much smaller niche.

Today, Apple reigns as the world’s most valuable brand with a market capitalization of nearly half a trillion dollars.

Competing in the ultimate leaderboard of brains and brilliance, how did Jobs accomplish this feat? Here are some clues:

1. FOCUS

Instead of letting product lines proliferate or permitting a thousand ideas to bloom, Steve Jobs insisted that Apple focus on just two or three priorities at a time, according to the best-selling biography by Walter Isaacson.

“There is no one better at turning off the noise that is going on around him,” said Tim Cook, now CEO. “That allows him to focus on a few things and say no to many things. Few people are really good at that.”

Jobs had a rigorous whittle-down process that started in a retreat with the top 100 people in the company. He would stand in front of a whiteboard and, according to the book, ask:

“What are the ten things we should be doing next?” People would fight to get their suggestions on the list. Jobs would write them down and then cross off the ones he decreed dumb. After much jockeying, the group would come up with a list of ten. Then Jobs would slash the bottom seven and announce, “We can only do three.”

2. Buck the Trend

There is a frenetic pace of activity inside companies today. Consider the ferocity of global competition and technologies that enable 24/7 access. Add this jaw-dropping statistic: Since 1989, more than 18 million jobs cuts have been announced, according to the outplacement consultancy Challenger, Gray and Christmas.

The mandate is to do more with less. Leaders, managers and individual contributors are straddling unwieldy ranges of responsibilities with minimal support resources — resulting in fragile bandwidths and decreases in workforce productivity, as reported by PricewaterhouseCoopers Saratoga Group.

At Apple, Jobs did the opposite. He did less with more, i.e., putting more effort into fewer initiatives.

“In order to do a good job of those things that we decide to do, we must eliminate all of the unimportant opportunities.”

3. Go for a Hit.

My former ad agency colleague Deborah Stapleton worked with Jobs for six years as outside investor relations counsel for Pixar. ”He was focused on hits, much like a musical producer. He would always say, we’ve got to make this a hit.” Thus he looked to build in a masterful formula of performance features and design elements that would deliver a high level of market enthusiasm and customer delight. Other companies focused on quantity and variety, pumping out volumes of products and line extensions.

According to the Isaacson book:

” …he would care, sometimes obsessively, about marketing and image and even the details of packaging. ’When you open the box of an iPhone or iPad, we want that tactile experience to set the tone for how you perceive the product.’ “

4. Be Curious.

Jobs was constantly collecting input from diverse sources, Stapleton reports. ”I didn’t see him dismiss an idea out of hand,” she says. ”He listened, evaluated and decided.” He explored outside the business/technology box — with an appreciation for music, creativity and the visual arts. He was influenced by the zen of simplicity.

5. Dump the Dogs.

The Newton was Apple’s early design for a tablet-sized personal digital assistant. It was ten years in the making, but did not deliver on the goal to re-invent personal computing. When Jobs gained control of the company a second time, he did not want to build a new product on an erroneous foundation. He wanted to ditch the Newton architecture and start fresh.

“Shut it down, write it off, get rid of it. It doesn’t matter what it costs. People will cheer you if you got rid of it. “

6. Pursue the White Space

By clearing the decks, Jobs could target unoccupied territory that offered high opportunity. Apple was successful in crossing industry lines to penetrate new sectors and create new categories — a sneak attack on those facing inward in the silos.

The iPod upended the music industry. The iPhone stole business away from mobile, cameras and fired up a whole new market for apps. The iPad became the Big Daddy of gamechangers: eReader. Show-and-tell device. Near laptop functionality. Fit-in-your-purse convenience. It hooked tens of millions of fervent new users into the Apple world. And here’s the brilliance of Job’s compatibility conundrum: Kludgy syncs with BlackBerries and PCs drove additional migration to iPhone and Mac.

7. Too Much can Miss the Mark

The writer Malcolm Gladwell, who probed secrets of success in the best-selling book Outliers, suggested in a talk to the Association of American Publishers that many professions need essentially editorial skills. This from Publisher’s Marketplace:

In terms of national security, “…We didn’t have too little information [before 9/11], we had too much. We needed an editor…to take what mattered and throw out what didn’t matter.” 50 years ago, all you needed was a spy plane. Today you need something much more sophisticated–you need an editor.”

In another real-world example, Gladwell painted Steve Jobs’ great skill as editing down to what was most important. Gladwell said “an expert’s job is to place limits and impose standards” and “it’s the editor who is the king.”

8. Curator of Not-Invented-Yet

Jobs could see how components of design and innovation could be combined and calibrated to be presented optimally in products that no one ever imagined. He had the genius of creating demand for something you didn’t know you wanted — at a premium price, to boot.

Individually, these strategies are not earth-shattering, but combined, they are transformational. What will work for you?

copyright 2012 Nancy Keene All Rights Reserved

October 5, 2012